From its earliest recorded usage as a staple folk remedy to today’s modern era of its growing popularity, the idea that there is health in a cup of Rooibos has a long history.

This article provides an overview of historical and anecdotal reports of the health-giving properties of Rooibos, and details how its purported benefits – initially ignored by science – have become the focus of a growing number of researchers and health practitioners.

It’s Always Been Good For You

Mrs Moloko Temo lived for 134 years. At least, that is what she told everybody. If you doubted her, she could show you her ID with the birth year 1874. This blind woman from the village of Ga-Mamohwibidu, in northern Limpopo, had nearly sixty great-grandchildren. She last voted in the general elections just before she passed away in 2009.

The secret of her longevity? Exercise and eat good food, she said. In the mornings, Temo helped herself to freshly baked bread and a cup of rooibos, and for lunch she had maize porridge with milk and African spinach.

The old lady from Limpopo has a kindred spirit on British TV: Carol Vorderman, a game show host and bestselling author of book on dieting, who believes that rooibos can help you look younger and feel healthier. This tea is an ingredient of her Detox plans, to be counted as part of the daily fluid intake.

Across the pond, celebrity surgeon Dr Oz recommends having rooibos tea before bedtime. ‘It’s loaded with antioxidants,’ he writes, ‘and studies show it reduces tension, irritability and headaches – all key components linked to insomnia.’

Most people who drink rooibos know that it is good for you. Tea, whether it is herbal or Camellia sinensis, has been associated with health for centuries. In the earliest-known British advertisement for tea, published about 360 years ago, owners of Sultan’s Head, London, assured their patrons that the new beverage was ‘by all Physitians approved’.

Marketers like to bolster their emotional sales pitch with a rational ‘reason to believe’. This approach has always worked for rooibos: health aspects have been part of its advertising from the salad days of the industry.

Kellogg’s rooibos

At the South African Exhibition in London in 1907, Rooibos tea was hailed as having a ‘soothing effect upon the system. Dyspeptics [those who suffer from indigestion], and those troubled with nervous disorders, drink this charming beverage with impunity.’

James Hartley’s adverts from the Cape Times in that period were more categorical: he asserted that rooibos was ‘a certain cure for indigestion and nervous disorders’. Because of these qualities, the main hospital of the Cape Colony was using ninety kilos of rooibos a month.

The praise reached the ears of Dr John Harvey Kellogg, Medical Director at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, US. A zealous champion of vegetarianism and healthy lifestyles, he loathed drinking and smoking. The six-storey fireproof brick ‘San’, the world’s largest institution of its kind, was developed by him as a ‘place where people learn to stay well’.

Kellogg often went overseas on the lookout for new techniques and products that could profit his 1,100 patients at Battle Creek. ‘He walked in the morning dew with German naturopaths’, writes his biographer. ‘He collected beans in Peru, which were three thousand years old, and acquired an enthusiasm for the edible soybean which his fellow countrymen stubbornly refused to share.’

The different products Kellogg unearthed abroad or invented (cornflakes, peanut butter) found their way into the diet of his patients. The most popular ones were manufactured on a large scale by Battle Creek Sanitarium Health Foods and distributed to leading groceries, department stores and health-food shops across the country.

Caffeine drinks were not tolerated at Battle Creek, as Kellogg’s dietary system was entirely stimulant-free. His patients started their day with cereal coffee. Before World War 1, he had discovered rooibos. He saw this tisane as an excellent substitute for tea: it did not have an iota of alkaloids. What is more, the beverage tasted similar to tea, and palatability was an essential characteristic of health foods, according to Kellogg.

‘The African drink,’ Battle Creek adverts declared, ‘has the aroma and refreshing qualities of the best tea and is free from poisonous caffeine and tannic acid which causes insomnia, headaches and digestive disturbances.’

Rooibos was served at breakfast in his sanatorium, and Kellogg even designed health-food recipes with it.

The absence of caffeine remained the only publicised health benefit of this beverage until the late 1960s. Dr Nortier, the father of cultivated rooibos, prescribed the tea to those afflicted by heart ailments, insomnia, indigestion and high blood pressure.

Specialists from the Fruit Research Station in Stellenbosch, who spearheaded rooibos research in the late 1940s, endorsed it as a wholesome tea substitute to be consumed by children and adults with ‘digestive or heart troubles’.

Traditional knowledge

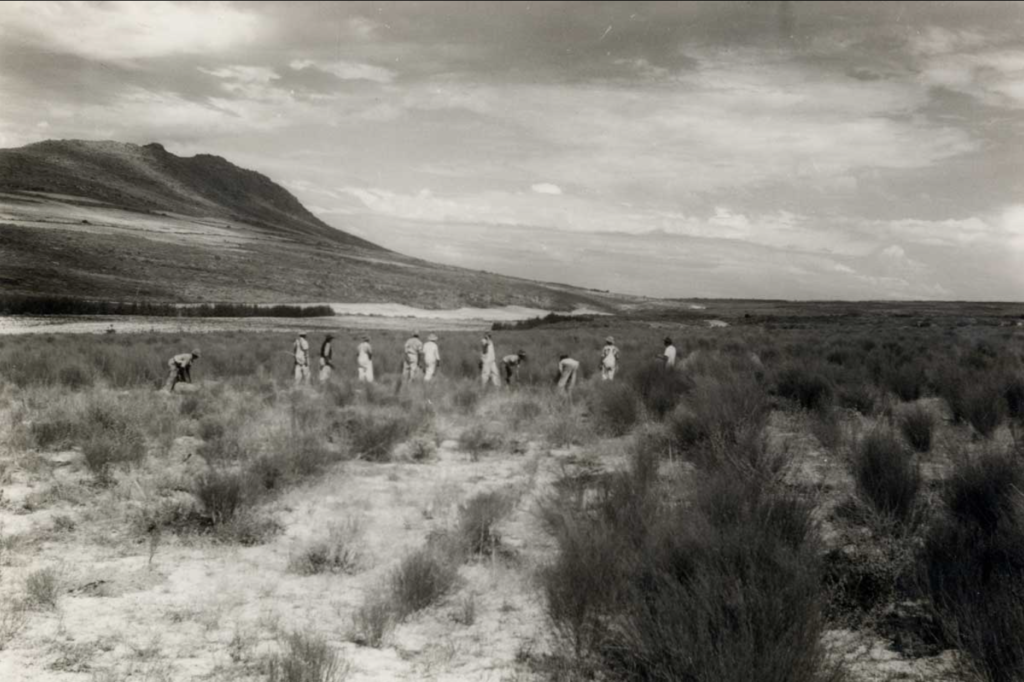

The idea that rooibos could provide some therapeutic benefits had probably emerged long before James Hartley or Benjamin Ginsberg first glimpsed the peaks of the Cederberg mountains.

In the Cape, particularly in its remotest parts, traditions of herbal medicine were very strong. ‘Surgeons, apothecaries, and others, when they cannot find in this country the usual and genuine medicinal plants, look for others that somewhat resemble them, either in their flowers, leaves, smell, or general habit, and then give them the same names’, wrote Carl Thunberg, an 18th-century Swedish botanist who travelled in the colony recording folk remedies. To visit a doctor, you had to go to the village many miles away. Otherwise, you made do with whatever was there in the veld.

Along with patent ‘Halle’ and ‘Old Dutch’ medicines comprising imported components, farmers kept local herbs in their medicine chests, such as buchu, wild wormwood or bitter aloe. Some of these indigenous plants had been proposed by their San or Khoikhoi servants. People of the Cederberg area knew the tricks of spotting medicinal plants just as well as they knew that bee excrements on rocks would lead them to a beehive full of honey.

Awareness of the healing properties of local species have been common in rural areas to which they are endemic.

People in the Cederberg region or in the Suid Bokkeveld learn how to use them from childhood from their parents or grandparents. By asking the oldest of them about it, one might get an idea of how rooibos was utilised in their area a hundred years ago and maybe even earlier.

A government-commissioned survey of traditional knowledge associated with rooibos has shown that many respondents in the Cederberg region used the A. linearis infusion or decoction for medicinal purposes.

According to Johannes Ockhuis, a small farmer from Heuningvlei, rooibos was regarded as a ‘very good remedy’ even when he was a boy in the 1930-1940s. ‘Using it was much easier than going to a doctor’, he explains. ‘If you were poor and had no money, you had to make use of the herbs that grew in the area. And often, it was more successful than using proper medicine.’

Interviews done in the original rooibos-growing areas, and those conducted for the government-commissioned survey, show that rooibos tea has been employed by local communities for the following conditions:

• abdominal pain;

• indigestion (‘upset stomach’) in babies and adults;

• dermatophytosis (‘ringworm’);

• rashes in babies and children;

• restlessness in babies (sedative, mild soporific action); and

• poor lactation.

Rooibos can be applied on the skin, for instance, in case of rashes. Some people even bath in this tea. Barend Salomo, the manager of the Wupperthal Original Rooibos Cooperative, learnt about rooibos bathing as treatment for eczema from his mother, who was born in 1918.

Babies’ friend

To help small children against colic, anxiety or restlessness, parents give them rooibos tea – together with or instead of milk. Abraham Ockhuis of Heuningvlei (born in 1953) says that blending milk and rooibos in a bottle and feeding babies with that mixture has been done in his family for generations to stop infants and toddlers from crying or to stimulate their appetite.

In her collection of South African natural remedies, submitted by two thousand people from all over the country in the 1980s, Betsie Rood noted that both rooibos and honeybush were good for mothers because these tisanes stimulate milk production. Babies can drink rooibos tea in addition to or even in place of breast milk. You can also replace mother’s milk with this tea when weaning.

‘If babies are crying, you give them rooibos’, says Christo Nieuwoudt (born in 1935), a farmer from the Cederberg region. His labourers used to do it when he was young – they mixed donkey milk with rooibos and fed it to infants.

Overall, locals believe that rooibos tea relieves all kinds of abdominal conditions. Petrus Hanekom (born in 1940) of Bosdorp, near Algeria, told me that ‘people say, “don’t drink coffee, have rooibos tea” if your stomach is sore.’

This view existed even in the early twentieth century. In 1949, a popular South African daily remarked that ‘old people …. strongly believed that [rooibos] was good for the stomach.’ According to a South African magazine from that period, it was thought that children should drink rooibos ‘because it was healthier than the shop tea that gave children “fleas in the stomach” [upset their stomachs]’.

Some of the medical workers in the Cederberg area were also aware of these virtues of rooibos. Olive Nieuwoudt (born in 1932), a trained nurse and midwife married to a local farmer, claimed that she gave rooibos tea to children troubled with gastroenteritis in the 1950s. ‘There were no doctors in our area, so mothers came in from ten kilometres away with their children to our farm’, she recounted. ‘I used to have the children drink rooibos, and they walked out feeling better.’ There was always wild rooibos growing on their farm, Kromrivier, and the family collected it. Nieuwoudt’s mother-in-law taught her how to treat babies with rooibos tea.

This body of traditional knowledge was unknown outside the Rooibos Country and, when scientists at last began to investigate the medicinal properties of rooibos tea, they started from scratch.

A health beverage officially

The industry repositioned rooibos as a health beverage after Annekie Theron’s discovery. In the early 1980s, and on the back of the growing popularity of the Annique brand of rooibos beauty products she created, she travelled to Japan with talks on her experiments with colic babies. Japanese academics decided to probe the benefits of rooibos tea.

In 1984, James van Putten, the chief operating officer of the Rooibos Control Board, also went to Japan. He met experts in antioxidants, who were intrigued by the anti-ageing potential of flavonoids in rooibos. This led to the launch of this beverage in Japan as a high-priced medicinal tea.

In 1994, the rooibos industry asked Elizabeth Joubert – a young food scientist from the Institute of Fruit and Fruit Technology, Stellenbosch, who had done both her MSc and PhD on aspects of rooibos processing – to investigate the antioxidant activity of this tea. To make the project more interesting for her student’s post-graduate project, it was decided to compare unoxidised and semi-oxidised plant material. The unoxidised kind showed higher antioxidant activity, which, eventually, lead to the introduction of green (unoxidised) rooibos to the market.

Professor Brian Koeppen – Head of the Department of Food Science at Stellenbosch University before 1981 – sparked Joubert’s interest in aspalathin, as it was included in his Food Science course notes on flavonoids. In the late 1950s and the early 1960s, he had isolated and identified aspalathin, novel to rooibos.

Joubert has been regularly engaged in rooibos product research since 1983, and her cooperation with the industry continues. Until the late 1990s, she was the only scientist consistently investigating rooibos. Publication of her scientific papers in international scientific journals helped to create awareness of this beverage among scientists worldwide. Ever since, scholarly papers on antioxidant activity of herbal teas are almost guaranteed to refer to rooibos or include rooibos as a “benchmark”. One of Joubert’s early articles on the antioxidant activity of aspalathin appeared in an American Chemical Society publication. ‘It’s from 1997, and I’ve done better work later,’ she says, ‘but it is still cited.’

Many studies on rooibos and its qualities have been conducted in the last decades. Various postulations have been brought forward by scientists, marketers and opinion makers. In Britain, for instance, the Women’s Nutritional Advisory Service advocated rooibos tea for reducing muscle cramps during pre-menstrual syndrome. ‘As well as being an anti-spasmodic, it aids the absorption of iron and also magnesium, which is vital to the smooth running of the female cycle’, their spokesperson said.

Scientists agree that rooibos is harmless: it contains no caffeine, fat, protein, kilojoules, preservatives or colourants.

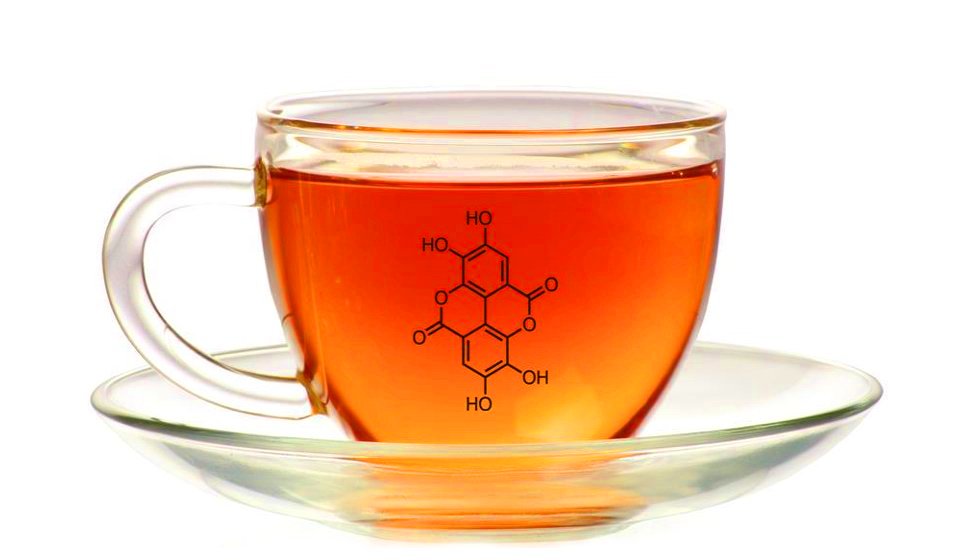

Antioxidants and aspalathin

Antioxidants have remained the most fascinating elements of rooibos. In Japan, their presence is among the main reasons why people buy this tea. Several studies, mainly based on in vitro experiments, have suggested that antioxidants in rooibos may help to prevent free radical damage that leads to cancer or heart attacks.

Rooibos has made it to the Time magazine’s list of ‘The 50 Healthiest Foods of All Time’. According to dietitian Tina Ruggiero, author of The Truly Healthy Family Cookbook, it is because this tea is ‘packed with antioxidants that guard us from chronic and degenerative diseases alike’.

Laune Erickson analysed over seventy scientific papers on rooibos for an American Botanical Council journal. She concluded that consumption of this beverage was free of side effects, and the tea itself showed a comparatively high antioxidant capacity. But the difficulty for researchers was to determine if or how the positive action they saw in the tube or in animals was translated into health benefits for people.

Professor Joubert, who continues to study rooibos at the ARC-Infruitec-Nietvoorbij in Stellenbosch, says that the beneficial effects of this tisane may be better interpreted when scientists, among others, understand the beneficial role aspalathin or its metabolites may play. This flavonoid, or polyphenol, has been found only in Aspalathus species. It is one of the most active antioxidants in rooibos tea.

After rooibos oxidises, much like the black tea, very little aspalathin is left in the leaf. And yet aspalathin remains a prominent flavonoid of an infusion of conventional rooibos. To save as many flavonoids as possible when producing green rooibos, the tea is either steamed to inactivate enzymes or dried in a cold and humid air before shredding.

Apart from revealing the mode of operation of aspalathin, researchers need to know to what extent the flavonoids in rooibos tea reach the systematic circulation of blood, and how they are absorbed and transformed in the human body. To confirm the health-promoting qualities, researchers need to do more studies on humans.

Research continues

To boost the marketability of rooibos, the industry needs substantiated statements relating to diet or beauty, as such statements are a major driver of consumer purchasing decisions of tisanes. Consumers have turned to beverages that can change their mood or help them feel better through a therapeutic action – they have started linking what they drink with brain functions.

According to Adele du Toit of Annique, who oversees the marketing efforts of the Rooibos Council, the health properties are the best platform for rooibos tea. ‘I implicitly believe in its healing power’, he says. ‘We have sufficient circumstantial and some scientific evidence to substantiate many of the claims. But we need to take them to clinical trials.’

The current Rooibos Council has sponsored several such projects, concentrating on the anti-inflammatory, anti-ageing, anti-obesity and cancer-preventing attributes of rooibos.

Some of the most exciting research priorities the SA Rooibos Council includes how Rooibos has displayed potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, redox modulating, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, cardiometabolic support and organ protective potential.

‘A Mercedes-Benz Sold as a Beetle’

Joe Swart of Joekels oversees research at the South African Rooibos Council. His task is to validate such claims so that marketers like him would have something to put on their packs.

‘Our aim has been to elevate the position of rooibos based on scientific facts’, he says. ‘This tea has been a Mercedes-Benz sold as a Beetle. The more we examine it, the more we find what a wonderful product it is. We know that rooibos works, but we’re still trying to understand why it’s so effective.’

As additional research is conducted and ongoing discoveries of the nutritional compounds found in Rooibos are confirmed by researchers in both South Africa as well as worldwide, the standing of Rooibos internationally continues to grow. Though wild claims of its health properties should still be viewed with a critical eye, the growing body of evidence appears to confirm what the old-timers of the Cederberg and many drinkers of this indigenous South African herbal tea have long known.

A Tea Whose Time Has Come

With this body of evidence showing no sign of abating, it would be reasonable to assume that in the years to come, advances in research into Rooibos will provide a much clearer picture of how its unique compounds are of benefit, and may even go on to become the focus of groundbreaking clinical applications.

Though a relatively nondescript plant in the greater botanical scheme of things, what is certain is that Rooibos holds significant potential as a result of the action of the range of phytochemicals found in it. With this prospect being increasingly validated as a result of commercial and medical interest, it would be safe to say that consumer interest in this humble but beneficial plant native to the Cederberg will continue to grow.

This article is an extract of ‘The Rooibos Story‘ by researcher Boris Gorelik and is published with the kind permission of the South African Rooibos Council.

Look out for forthcoming related articles in the series which will provide further insights into many aspects of Rooibos including the Rooibos industry, its health benefits and the global marketplace.