With significant colonial history and commercial ties to South Africa as far back as the 17th century, and with a well-established taste for tea, it stands to reason that rooibos would find a foothold in the United Kingdom early on. Britain must have been the first country outside Africa to get a chance to know rooibos tea, which debuted in 1907 at the South African Exhibition in London.

Earliest attempts

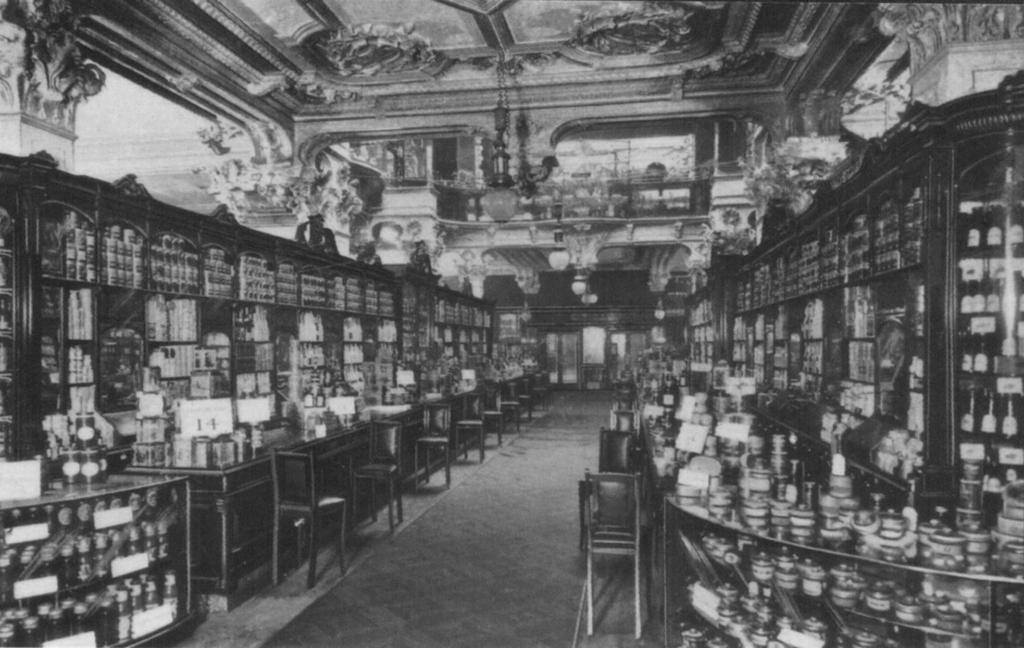

The only order received as a result of the Exhibition was from Robert Jackson’s company. You may have heard about Jacksons of Piccadilly, a Fairtrade-certified tea brand with a low profile, one of the many in the Twinings stable. But a century ago, it was a venerable tea house, bestowed with Royal Warrants, and self-styled originator of the Earl Grey mixture.

The ordered amount of 54 kilos was promptly prepared, processed and shipped to London. Robert Jackson did manage to sell it, but the South Africans lost out on the transaction, because – as the consignment cost far more than the same quantity of top-grade black tea in Britain – Jackson priced it below its real value.

The Cape authorities concluded that, even though rooibos tea was being admitted into the British Isles free of duty, it had no future on the London market.

The Imperial Institute, engaged in research for the benefit of the dominions and colonies, expressed a similar view. In 1917, the South African Trade Commissioner asked the Institute to analyse the chemical composition of rooibos. World War 1 was in full swing, and the British Isles could not get enough Asian tea. The trade commissioner wanted to know if rooibos tea could step into the breach.

This potentially was the first time that the A. linearis infusion was examined by professional scientists. Having completed their study, they pronounced:

‘It seems doubtful whether this material would be acceptable in the United Kingdom as a substitute for ordinary tea, as it contains no caffeine or other alkaloids and would consequently not have the stimulating effect of tea.’

The taste of rooibos did not resemble Asian tea closely enough, and the beverage contained no stimulants. Therefore, it was inferior to the Camellia sinensis in every way. ‘Rooibos tea has no chance’, decided the South African officials and dropped the matter.

This does not mean that the attempts to prove its worth in Britain were abandoned. Caspa Tea used to send out samples of their product to big tea merchants and retail establishments, both directly and through the South African Trade Commissioner, in the mid-1920s. Harrod’s, an upmarket department store in London, requested a trial consignment of thirty kilos, but it is uncertain whether any sales came out of it.

Sizeable quantities of rooibos tea reached the UK only after World War 2, and Seventh Heaven Products of London made an early consistent effort to launch rooibos there. They christened it ‘Lowtan’ and placed advertisements in The Times, the Spectator and dozens of other papers, as well as in magazines for vegetarians and the health-conscious.

But their timing was wrong. After Seventh Heaven received their first half tonne, a severe drought began in the Cederberg region, and the Rooibos Board curtailed their export permit. The company had disposed of the initial quantity and could not get more tea to sell.

They pleaded with the South African government to persuade the Board to let the Wupperthal Institute send them a tonne of rooibos tea. ‘[I]t seems to us a pity if there is not a continuity of supply’, they wrote in 1959: ‘because there will come a day when this will be a very big product which will be to South Africa’s advantage …. We have, at the moment, only attempted to sell to people who are either vegetarian or who suffer from some heart or stomach complaint, but it is quite clear that Rooibos Tea can have a wider appeal.’

There is no evidence that the permit was ever granted. Seventh Heaven gave up on rooibos, which had to wait another twenty years for an introduction to the British public.

Bruce Ginsberg: Learning the way of tea

In the mid-1970s – when the rooibos industry experienced a surplus – Bruce Ginsberg, the fourth generation of the family involved with rooibos, moved to the United Kingdom. Apart from furthering his East Asian studies, he tried to open a market for the South African tisane.

Over the decades, his father Chas had attempted to export his rooibos to Britain but never managed to secure a firm foothold there. Odd shipments went, but the beverage never caught on.

By comparison with his down-to-earth, matter-of-fact father, Bruce was a romantic. He wrote poetry, but his passion was painting: he even considered going to an art school. His father objected, ‘Painting is what you do on a Sunday. You don’t want to be a struggling artist.’

Bruce became a painter by night, taking evening classes, and a journalist by day, working on the Cape Argus. He boarded in the Gardens in Cape Town with the elderly mother of the famous Afrikaans writer, Uys Krige. Staying with Bruce, on the top floor of the house, was his colleague, David Coetzee, whose brother – novelist J M Coetzee – later won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The stint at the Cape Town newspaper proved a useful training period for Bruce, but he had a great interest in exploring Asian culture. His soul was yearning for adventure: an adventure of self-discovery.

One day, Bruce horrified his parents when he announced his departure for Asia. He had secured an interview with the English edition of the Yomiuri, a major Japanese newspaper in Tokyo. He did not know if he was ever coming back.

Ginsberg left home at twenty-one, heading for Hong Kong on an old Dutch passenger steamer that traded between South America and Japan. As befits a young man in search of wisdom, Bruce had intended travelling steerage. Yet his father would have none of that, ‘You have to travel in a cabin like a gentleman!’

He spent two years in Asia, writing for papers and studying local cultures. He spent some weeks flying in American military planes around conflict areas in Vietnam, with a view to becoming a war correspondent.

The other career option he favoured was to have a life of poverty as a Buddhist monk.

‘Many avant-garde abstract expressionist painters, Jack Kerouac and other creative people in the West, were looking to Zen for inspiration’, he remembers.

Among them was Gary Snyder, a famous ‘Beat’ poet and Pulitzer-Prize winner. Snyder translated literary works from Japanese and ancient Chinese and had for a period, in 1959, become a Zen monk, a highly disciplined practice favoured by Samurai warriors and painters, poets and garden designers.

In 1967, Bruce Ginsberg began his explorations in Japan, met Snyder in Kyoto and studied Zen at the Daitoku-ji Monastery, world famous for its magnificent gardens.

There is an axiom in Zen, ‘A day without work, is a day without food’. Physical labour was a critical part of Bruce’s fierce training. As part of his duties, he weeded the gardens, swept, washed and polished ancient cypress floors and cleaned lavatories. A layman initiate, he took part in the meditation training. He had to sit motionless for 40-minute periods for up to seventeen hours a day, watching the rise and fall of his own breath.

‘The state of mind needed was like the finger on a trigger taking aim: totally poised, balanced, relaxed and alert, and almost playful’, he remembers. ‘The same state of mind needed when drinking a cup of tea.’

Those who dared to budge, or requested it, had to endure being hit with a flat stick, the kusaku. ‘You treated the three blows on each shoulder like an ice-cold shower,’ he says, ‘a benign way of bringing you back to concentration when the mind wavered’.

At Daitoku-ji, Ginsberg learnt the ancient art and craft of tea, its tradition and culture of wisdom. Sometimes, through the long sitting periods, a small cup of tea would be served in a very formal way to the novices to help keep them awake. This infusion had a special meaning for the monastery.

Senno Rikyū, a 16th-century adherent of the Way of Tea, who formulated the main principles of the Japanese tea ceremony, had often visited Daitoku-ji. Every autumn, ten thousand teachers of tea ceremony from all over Japan stream to the temple. They honour Rikyū and other founders of the ceremony.

Later, after a time in Korean and Taiwanese monasteries, Ginsberg visited tea estates in Ceylon, bathed with the Hindus in the Ganges and studied in the Himalayas, drinking tea with Tibetans and Nepalese. It deepened his interest in the culture of this beverage. He became a remarkable tea expert and connoisseur.

To London with rooibos

From Asia, he decided to go to London, to look for a job as a reporter in Fleet Street. He returned to South Africa just to collect his suits that he had left in Cape Town. But his father had had a heart attack not long before, and Bruce found himself helping on Die Berg. He had to gather in the rooibos crop and grape harvest of nearly 1500 tonnes. With the family responsibilities heaped on him, Ginsberg had to stay on to run the farm. Making rooibos for several weeks every year gave him a practical understanding of the oxidation process.

In 1976, with his father’s reluctant co-operation, Bruce Ginsberg went to England to bring the good news of rooibos tea to the British. The rooibos industry was going through another period of overproduction. Before the domestic market began to demand more rooibos as the price of black tea increased, distributors in South Africa had been desperate to do away with the surpluses.

Ginsberg arrived in London at the age of thirty-one to open a new market and develop his notion of the ‘tea of the future’ to Western Europe’s conservative tea-drinking nation.

He faced a rather severe challenge: the product was totally unknown and unwanted, and Ginsberg had hardly any capital or funding. He set up a company of his own, Wistbray Ltd, to market the family brand Eleven o’Clock and bought rooibos from the old family firm, B. Ginsberg, initially on consignment.

Once in London, Ginsberg used his rapport with cultural perspectives of the day to frame a new vision for rooibos and develop a following. His Zen training, spiritual and broader tea interests were in sync with the growing ecological, health and social responsibility awareness and spiritual yearnings and explorations of the new generation.

The big British debut of rooibos took place in May 1977 at the first Mind Body Spirit Festival in London. Bruce and his wife Karin served thousands of cups of the South African infusion free of charge to visitors at the prime venue in the city, Olympia Exhibition Centre. Bruce, a former rugby player, was carrying huge canisters with water from the basement, to fill up the kettles.

People with an interest in natural healing and spirituality became the early adopters of rooibos in the UK. ‘These things were close to my heart, after my years in Asia’, says Ginsberg. ‘And we promoted rooibos as a very special, almost sacred tea of the indigenous people of the Cape.’

Ginsberg learnt that nearly all the British tea drinkers consumed black tea with milk, and the industry was hard-wired to cater for these tastes. Just five per cent of the tea consumers were intrepid enough to buy tisanes, but rooibos tea had never been on their shopping lists. Many mistrusted that strange ‘African herb’, as they could not be sure if it was safe. How could they know if conventional standards of hygiene were maintained out there in Africa?

In Britain, the beverage had been completely unknown, except to a few sceptical expatriate South Africans or Britons who had lived in South Africa but never tried rooibos.

Ginsberg went from health shop to health shop with rooibos in the boot of his car. ‘I’d get out and tell them the story of rooibos’, he remembers. ‘And they shook their heads. Few of them understood what rooibos was.’ He started writing articles for newspapers, health magazines and respected journals like the Herbal Review (British Herb Society) on rooibos history and botany.

Establishing the market

Most of the British consumers would have agreed with the Imperial Institute’s judgement from half a century before that the absence of caffeine in rooibos was a shortcoming. But Ginsberg saw it as a benefit. His Eleven o’Clock packets delivered the ‘caffeine-free’ message loud and clear.

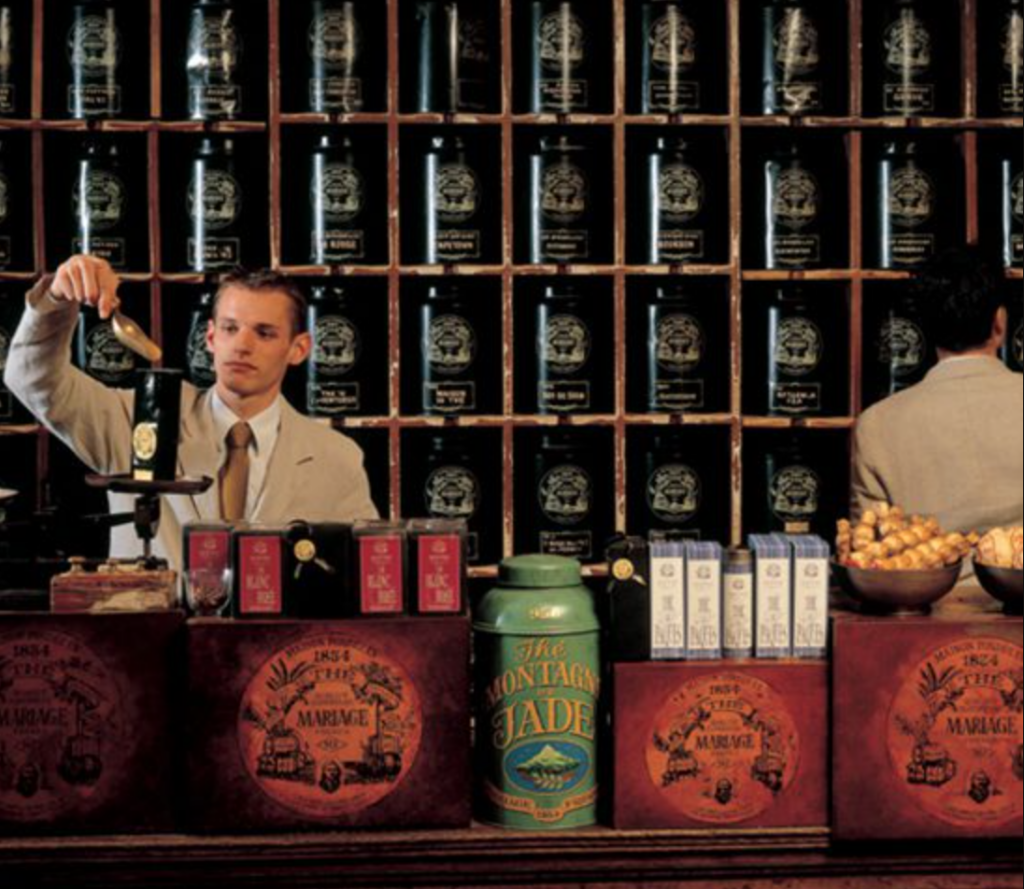

Besides, Ginsberg wanted to get the message across that rooibos was like conventional tea. It had gone through a sophisticated artisan curing process, similar to ancient Chinese techniques, and was not just a plain tisane. In Britain at the time, herbal teas were traditionally classified as dried leaves of a plant placed in water, but with rooibos an enzymatic action of oxidation had redefined the taste profile.

Initially, tea packers like Twinings tried to prevent tisanes from being labelled as ‘tea’ in the UK, and the tea industry closely guarded the Camellia sinensis. The Trading Standards Authority instructed Ginsberg to remove rooibos from sale until the descriptor ‘tea’ had been removed.

He protested and set out to prove to the inspectors that the Chinese words ‘cha’ and ‘tea’ referred to any plant infusions. A dedicated Asian scholar, Ginsberg demonstrated that such usage in Britain was noted by the Oxford University Dictionary. In Britain, tisanes had been known as ‘tea’ from the 1660s. The authorities accepted Ginsberg’s arguments. Rooibos was officially recognised as a tea in Britain and allowed to be labelled as such.

His first campaign, which got under way in 1977, featured testimonials by British nutrition experts and organic farming pioneers. Hilda Cherry Hills praised the naturally caffeine-free rooibos as a ‘godsend for many people in this country’. Her husband, Lawrence Donegan Hills – who founded the leading organic-growing charity, the present-day Garden Organic – hailed the South African product as ‘the tea of the future’.

‘When I started in Britain in 1976,’ remembers Ginsberg, ‘I had already decided that rooibos had to be special, in the way I perceived it, with my personal fascination with rooibos cultivation, Clanwilliam and all its inhabitants. I had been fascinated with Khoi culture. At the age of eleven, I painted my first imitation of a Bushman painting on a flat stone, which I still keep near my working table on a small farm in the English countryside, sixty years later. When I lecture at places like London University on meditational states and East Asian culture, I always include a slide of Khoi people hunting, and the special awareness and alertness states needed to be successful in stalking — an ancient form of meditational yoga.’

He took advice on rooibos positioning from a leading London marketing consultancy. Their recommendation to ignore its South African positioning as a cheap tea concurred with his own view. Rooibos was to be sold above the price of black tea. A family friend – great South African financier and marketer, Dr Anton Rupert – fully supported this provocative strategy. Rooibos had to be presented as a rare and special tea abroad.

This positioning allowed a comfortable margin, which could be re-invested in the critical promotion that was needed to get the product going. Pitching rooibos well above black tea proved particularly helpful in the early years, when the educated public in Britain — the target audience for rooibos — were outraged at apartheid and consequently avoided South African products. For years there were no profits, barely a livelihood, while Ginsberg’s young company sought sales.

They started participating in important shows in London with their new message about the sophisticated beverage. His company’s major contribution, Ginsberg believes, was to emphasise the caffeine-free nature of rooibos as well as its intriguing health benefits.

Rooibos gains a foothold in the UK

‘A tea’s effect comes in both its tasting and its subliminal “without realising” effect’, he says. ‘We crave a cup of tea because subliminally the body wants to resonate again, with its combined alertness (from the caffeine) and the relaxing effects (from theanine). Similarly, rooibos seems to have a pleasing effect to its drinkers. This potential mood effect needed highlighting in its promotion, a form of pleasure.’

When his father had commissioned clinical research of rooibos several decades before, the absence of stimulants was viewed as a negative by marketers. But Bruce Ginsberg made it rooibos’ strongest selling point. In his early days in London, he spent evenings at home with his wife, sticking blue labels on Eleven o’Clock packets that read, ‘Caffeine Free, Low Tannin content’.

Ginsberg kept a card system, with details of every delicatessen and health shop in Britain. He knew every shopkeeper’s name and phoned them regularly, sitting on the phone for many hours a day, chatting and exploring their perspectives and needs (or ringing off quickly if they were serving a customer). He had learnt persistence during his training at the newspaper, where a contacts book with telephone numbers was the prerequisite for every journalist. His writing ability served him well when he produced the publicity material for his business.

‘At some point, we started offering rooibos to shop owners free’, remembers Ginsberg. ‘We would say, “Take ten packets, put them on the shelf with our leaflets. If you sell them, we’ll invoice you.” And the sales gradually started to grow.’

By the mid-1980s, rooibos tea had become a fixture of the speciality and ethical food shops. It also appeared in mainstream venues. A London-based South African wrote to the Rooibos Board:

‘Exclusive stores like Harrods and health food shops offer it as a calming herbal tea; and even department stores like Selfridges. I have to pay 59p for 250 grams at Harrods and slightly less at Selfridges, but I’m quite content, because we can drink as much rooibos as we want.’

The Board, going out of their way to augment exports under the international embargo, invented a publicity stunt. Sarah Ferguson had just married Prince Andrew, becoming the Duchess of York and daughter-in-law of the British Queen. The Board sent a package of rooibos to her. The tea was supposed to help the duchess and Princess Diana, advocates of healthy and natural diets, to stay fit.

On receiving a letter of thanks from the Royal Secretary, the Board announced to the press that the fame of rooibos tea ‘now stretches to the heart of Buckingham Palace in London, and even Fergie and Di know about it.’

Even earlier, at a health show in London in the 1970s, the Queen’s uncle and mentor – Lord Mountbatten, former Viceroy of India – spent time at the Eleven o’Clock stand, chatting to Bruce and Karin Ginsberg and sampling rooibos. The tea was also sent to Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, who enjoyed it at Kensington Palace in 1993.

Sanctions and competition

Meanwhile, the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, organised in response to the ANC’s call for boycott on South African goods, set in motion a massive campaign for economic sanctions. The government refused to concede, arguing that the punitive measures and withdrawal of British investment from South Africa would not force them to dismantle apartheid.

Be that as it may, goods produced in the RSA almost disappeared from the UK retail trade. Eleven o’Clock rooibos was an exception. ‘By the mid-1980s, our tea was available in every high street across Britain, in a thousand health and speciality food outlets and delicatessen’, recounts Ginsberg. ‘This was at a time of a very tough trading climate for any South African products. Protesters targeted shops that carried rooibos. They would put superglue in the locks.’

Ginsberg’s company quietly carried on, relying on the association of its brand with ethical trading. Rooibos grew in an economically marginal area, and the communities whose livelihood depended on it needed support. Ginsberg attended international conferences by the Social Venture Network, an international movement exploring ideas of responsible trading and ethical values in business, which made the profit as important as responsibilities to the entire supply chain.

‘We were perhaps the earliest lobbyist with the Rooibos Control Board for organic registration for rooibos, and later for the Fairtrade movement, and also became supporters of the Slow Food concerns’, says Ginsberg. ‘Our resources and profits from rooibos trading were discreetly devoted for several years in the mid-1990s to getting international support for a universal mass tree planting concept, which eventually was even taken up by the White House in its Greening of America initiative. Mother Teresa, HH the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu had agreed to be patrons of our Tree 2000 charity’.

The dominance of Ginsberg’s company in the small British rooibos tea market remained uncontested until the late nineties when this beverage was identified as the best-selling product in the country’s health shops.

Ginsberg chose not to place rooibos in supermarkets until it had a large and loyal upmarket following, which would generate its own demand as a trendsetting programme. He was wary of prematurely turning it into a supermarket commodity product, as he believed that it could damage its sales with independent retailers and even undermine their loyalty to the product. Supermarkets sought to undercut them, destroying their trade in products for which small traders had built a following.

Bruce Ginsberg, for all his admiration for the Khoi and the San, had removed the Bushmen reference from his rooibos proposition in the 1980s. He could not find a connection between the origins of the beverage and the ancient cultures of the herders and the hunter-gatherers in published travel and botanical accounts and anthropological surveys.

Rooibos becomes mainstream

The introduction of rooibos into supermarkets, accompanied by sizeable discounts and promotions, changed the image of the beverage for good. It paved the way for large commodity tea companies to jump on the bandwagon and start capitalising on rooibos.

In the 2000s, rooibos was lifted and carried forwards by a new tendency in the UK. Younger, relatively affluent audiences, discarded the monotony of conventional black tea drinking for the novelty and health attributes of green tea, and fruit and herbal tisanes. When purchasing Camellia sinensis, they opted for refined varieties: artisan, hand-made and single-estate. The more sophisticated those consumers were, the more often they tried new tea flavours, expanding their repertoire.

It had a halo effect on the mainstream market. Middle-of-the-road tea consumers became more adventurous in their drinking patterns. When demand for tisanes was surging in Britain in 2003-2007, the sales of rooibos tea tripled. One of the best performers, the South Africa infusion captured over eight per cent of the herbal tea market.

In 2007, Tetley, Britain’s number one tea brand, added rooibos to their range. At that stage, they still considered it ‘really quite a niche product’. After several years and nationwide marketing campaigns, Tetley were selling three hundred tonnes a year.

Once the other big companies woke up to the fact that rooibos was growing rapidly, it became a mainstream product. All supermarkets cottoned on to it, and now they offer at least three or four brands of rooibos.

Towards the end of 2016, most of the leading British tea manufacturers – from Twinings and Tetley to Clipper – had at least one rooibos variety in their ranges. Furthermore, most supermarkets had their own house brands of rooibos.

According to Bruce Ginsberg his company, Tea Times Trading, had the largest share of the rooibos tea market in 2017, but the commoditising of rooibos into supermarkets has undermined the rooibos growth pattern. Eleven o’Clock, the heritage brand, continues to sell, labelled ‘Original Rooibosch’ in the UK. Nowadays, it is mainly represented in health shops, selling to its loyal consumer base of the past 40 years.

Tea Times’ best-selling brand is Tick Tock. Launched in 2005, it is organic-certified and GM-free. Its packing and website were designed by David Hillman, a Royal Designer for Industry. The stylish retro-influenced look is a reason, according to Ginsberg, Tick Tock is Britain’s leading rooibos brand.

Rooibos is also part of his premium Dragonfly range, along with some of the novel and fine artisan teas from China.

One of the few British traders who know their growers personally, Bruce explores regional tea cultures, scouting for the finest teas affordable to the British, who are now accustomed to drinking cheap industrially manufactured black tea rather than handmade, artisan Slow Food-style varieties.

Over the past twenty years, Ginsberg has annually visited tea gardens in remote mountains in all regions of China, observing local and regional techniques of curing and processing fine teas.

Rooibos tea is adaptable, to its great advantage. ‘Although I’d say that plain rooibos remains our biggest seller,’ says Ginsberg, ‘there’s a growing trend in the UK for flavour. Flavoured speciality teas have shown an 8-10% growth. Rooibos is well placed in this context, because it’s not an acquired taste and it blends well with other ingredients.’

Current positioning

The British industry has set rooibos tea apart from the other tisanes. It is still an individual category within the speciality tea sector, with a value share of 2% of the UK tea market. Besides, rooibos comprises about 16% of the caffeine-free tea market.

Rooibos tea is now positioned in Britain as a speciality tea for the top-end AB1 market segment of top-end discriminating shoppers. It is enjoyed by trendsetters, health and sports practitioners, and by those who wish to reduce caffeine uptake. It is a smart tea to drink. Many coffee and sandwich bars offer rooibos, and it is still sold in foremost London luxury shops like the Harrods and at Selfridges food halls.

Yet the sales volumes have been decreasing, as the recent drought in the rooibos-growing areas reduced the yields, causing exporters to up their prices. These have reached nearly unsustainable levels. That is why some packers in Britain have stopped investing in promotion, or simply dropped this tea from their ranges or delisted it in supermarkets.

However, Bruce Ginsberg says that his original positioning of rooibos as a ‘rare and special tea of the future’ has been compromised by mass-marketers. But this specialist image once made Eleven o’Clock perhaps the first South African branded food or beverage product, other than wine, to find a permanent place in the British market. Corporations force rooibos prices down, allowing it to be a commodity, instead of leveraging the proposition of its rareness and special nature due to its limited production availability and often short supply.

Over the years, supermarkets trashed the retail prices for rooibos, forcing margins down. Consequently, because they could not compete with supermarket prices, many speciality shops have discontinued rooibos. It has left the rooibos market in the UK diminishing. In the end, manufacturers get little return, retailers refuse to accept price increases, and large tea companies tend to use rooibos only for short-term gain.

Ginsberg believes that the international marketing model for rooibos needs to be bringing much higher permanent prices and social benefits for producers and the dependent grower communities. In his opinion, treating small-production rooibos as a supermarket commodity prevents it from commanding much higher prices permanently as a speciality tea. This marketing model would allow drought-caused deficit periods to be managed for the benefit of all.

However, so far, the rooibos tea category has been gradually devalued in the eyes of the British consumer. Large profit-driven supermarket chains cut prices, dramatically reducing the producers’ and packers’ profit margins. At the same time, they have launched their own house-label rooibos varieties, further undermining the market. Such house brands are more affordable than the established brands, but their quality often leaves much to be desired.

There is a heavy corporate pressure on the market to abandon the niche positioning of rooibos and turn it into a short-term supermarket commodity, oblivious to its problematic production and unstable supply.

Meanwhile, rooibos is not an industrially manufactured tea or coffee, cultivable around the world. The Aspalathus linearis is restricted in its habitat by specific climate and cultivation requirements. This, in the context of the international demand for rooibos as far as production regions, foresees no major change in the location of production any time soon.

What is evident is that though it faced some initial challenges in becoming established in the United Kingdom as an alternative to black tea, rooibos is now firmly entrenched in this market and region. With the UK public having developed a taste for it, and with many leading tea companies maintaining stocks and adding new variants thanks to rooibos’ adaptability to flavouring, it is anticipated that the demand for rooibos will continue to grow.

This article is an extract of ‘The Rooibos Story‘ by researcher Boris Gorelik and is published with the kind permission of the South African Rooibos Council.

Look out for forthcoming related articles in the series which will provide further insights into many aspects of Rooibos including the Rooibos industry, its health benefits and the global marketplace.